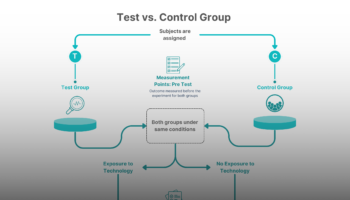

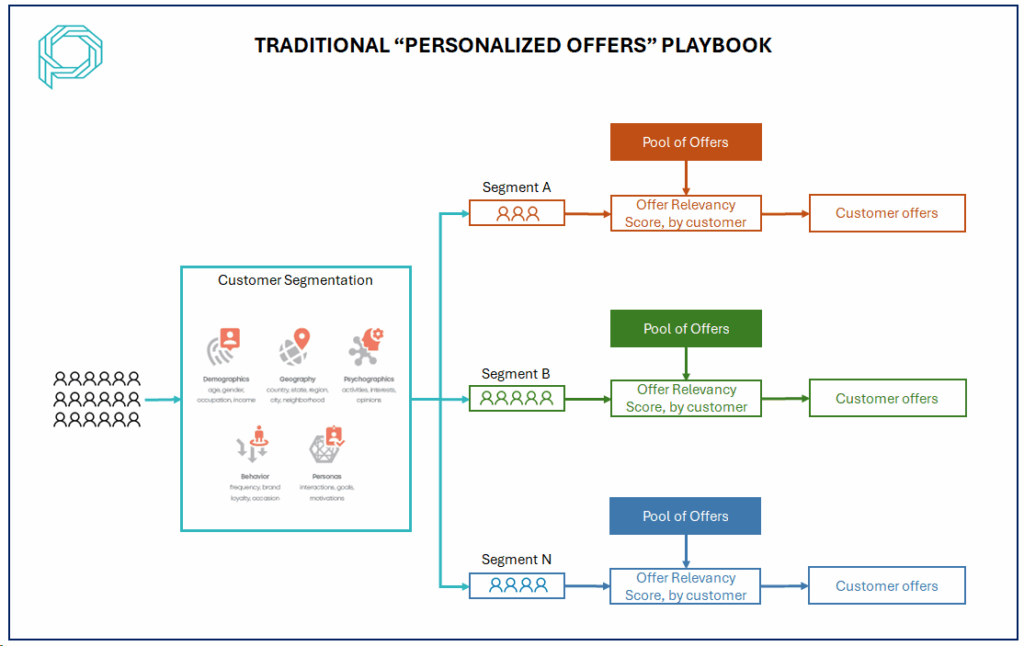

In practice, however, systems are rooted in segments and follow a familiar three-step playbook:

Step 1. Define segments

Step 2. Assign a fixed pool of offers to each segment

Step 3. Deliver "personalized" offers.

The system computes an offer relevancy score for each customer-offer combination within their assigned segment. Offers with the highest scores are then delivered to the customer.

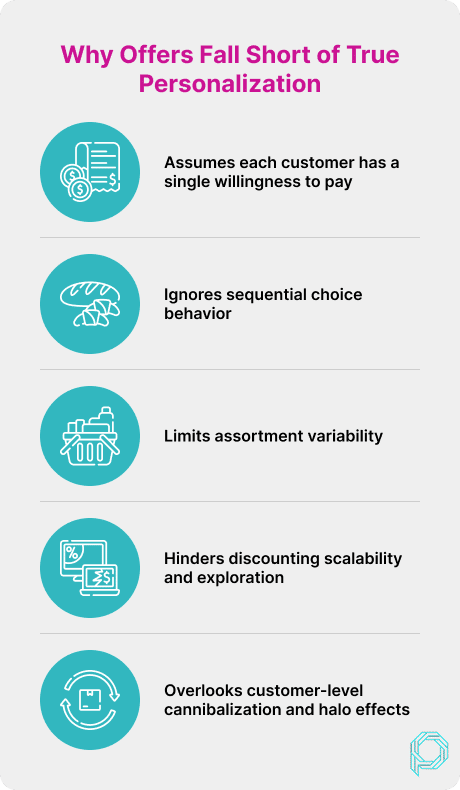

1. Assumes each customer has a single willingness to pay.

In reality, willingness to pay is product-specific. A customer may be highly price sensitive when buying organic chicken, yet price plays no role in their purchase of premium coffee.

2. Ignores sequential choice behavior.

Spending $40 on poultry per month could mean one stock-up trip or four weekly replenishment visits. Same total spend, but vastly different routines — one calls for timing-based offers, the other for basket-building. Treating both customers as the same leads to mistimed and ineffective incentives.

3. Limits assortment variability.

The fixed offer pool represents a small fraction of the grocer’s full assortment, which includes tens of thousands of SKUs. As a result, grocers fail to deliver offers on products that meet a customer’s unique preferences and needs.

4. Hinders discounting scalability and exploration.

The fixed offer pool constraints the grocer’s ability to explore varying discount levels to influence each individual customer’s behaviors. Afterall, the goal is to influence these behaviors at the lowest discount possible.

5. Overlooks customer-level cannibalization and halo effects.

Every discounting decision should be evaluated based on its incremental impact on revenue and gross margin while accounting for cannibalization and halo effects — at the individual customer level.

Move Beyond Segment-based Approaches and Embrace True 1:1 Personalization.

Schedule a free strategy session to discover how Polymatiks can help you reimagine personalization to drive customer engagement, loyalty, and sustainable growth.